What is an ecosystem? Comparing industrial and academic perspectives

A terminology swamp

As I wrote in the last post, in June I participated in the first two live conferences of my PhD.

At ISPIM, I presented a preliminary study on Technology Social Ventures (TSVs), namely companies with a social mission and a tech-based strategy, taking an ecosystem perspective. Instead, at EURAM, I shared the findings of a work focusing on the entrepreneurial level, to understand how TSVs manage the social and technological component of their strategy.

Photo taken during my presentation at ISPIM 2022, Copenhagen

Based on that, you may have realized that my main research interests lie at the intersection between technological innovation, societal challenges and ecosystems. Today, I would like to talk about this last topic.

Indeed, taking inspiration from the conversations I had at ISPIM conference, I realized:

- First, how difficult it is explaining what an “ecosystem” is to someone not working in the field.

- Second, scholars apply this concept in different ways and contexts, not always highlighting the differences.

- Third, despite its wide adoption in the industry, practitioners usually refer to the classic conceptualization of business ecosystem, neglecting the other definitions identified in the literature.

Therefore, in this blog I would like try to address this mismatch providing a brief overview on what characterizes an ecosystem, according to the literature.

Why

But before that, why are we even talking about ecosystems in the management literature? To answer this question, we should go back to the early 90s, when J.F. Moore adopted a Darwinian perspective to describe market competition’s dynamics. He argued that:

“Successful businesses are those that evolve rapidly and effectively.”

That is, those who are best able to adapt to the environment. Yet innovative businesses can’t evolve in a vacuum.

In fact, drawing from other recent anthropological and biological discoveries, he suggests that a company can be viewed not as a member of a single industry but as part of a business ecosystem that crosses a variety of industries (Moore, 1993).

However, the diffusion of this concept remained latent for almost a decade, until Iansiti and Levien (2004) recalled it in their HBR Article titled “Strategy as Ecology”. Finally, it is a few years later, when Adner (2006) showed how most traditional companies fail to commercialize breakthrough innovations in isolation, that the ecosystem concept definitely took hold.

Most likely, one of the enabling factors of the increasing adoption of this term in the late 2000s is the advent of digital technologies. Accordingly, collaborations between organizations became easier and more frequent, making the proper management of interdependencies crucial, as predicted by Moore three decades ago.

What

That said, what is an ecosystem?

An ecosystem can be defined as “an interdependent network of self-interested actors jointly creating value” (Bogers et al., 2019). In other words, we can see an ecosystem as a set of organizations collaborating to offer a specific product or service, without having formal bonds or hierarchical relations.

However, ecosystems can take several forms, which makes our blog even more interesting (or complex, depending on the perspective 🙂 ). Here, I will briefly present four of them (Scaringella & Radziwon, 2018), starting from the most embedded in the geography literature to the most abstract one:

- Entrepreneurial Ecosystem:

- “a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship within a specific institutional context” (Stam, 2016);

- Example: Typically these studies examine a high-technology cluster or the linkage between universities and local companies, such as Silicon Valley.

- Example: Typically these studies examine a high-technology cluster or the linkage between universities and local companies, such as Silicon Valley.

- “a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship within a specific institutional context” (Stam, 2016);

- Knowledge Ecosystem:

- “users and producers of knowledge that are organized around a joint knowledge search, and as such need to be located in close proximity” (Järvi et al., 2018; Van der Borgh et al., 2012).

- Example: The High-Tech Campus Eindhoven (HTCE), in the Netherlands, served as the object of the study for Van der Borgh et al. (2012).

- “users and producers of knowledge that are organized around a joint knowledge search, and as such need to be located in close proximity” (Järvi et al., 2018; Van der Borgh et al., 2012).

- Business Ecosystem:

- “a system in which companies coevolve capabilities around a new innovation, developed by a focal firm. They work cooperatively and competitively to support new products, satisfy customer needs, and eventually incorporate the next round of innovations” (Jacobides et al., 2018; Moore, 1993).

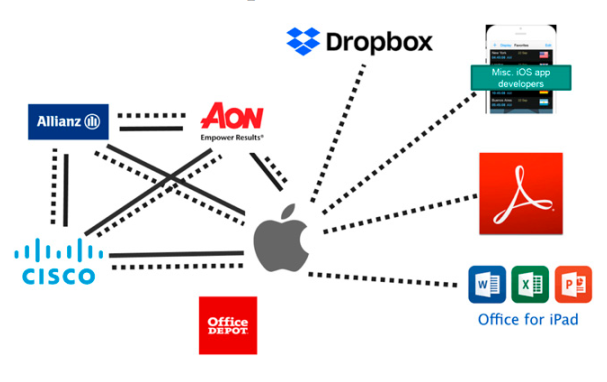

- Example: Apple is the leader of an ecosystem that crosses at least four major industries: personal computers, consumer electronics, information, and communications (Moore, 1993).

- “a system in which companies coevolve capabilities around a new innovation, developed by a focal firm. They work cooperatively and competitively to support new products, satisfy customer needs, and eventually incorporate the next round of innovations” (Jacobides et al., 2018; Moore, 1993).

- Innovation Ecosystem:

- “the alignment structure of a set of actors with varying degrees of multi-lateral, non-generic complementarities that are not fully hierarchically controlled, providing components and complements, in order for a focal value proposition to materialise” (Adner, 2017; Jacobides et al., 2018)

- Example: Digital platforms such as the Apple Store can be described as innovation ecosystems. Instead, the Michelin’s PAX run-flat tire system presented by Adner (2017), represents an example of a non-platform based ecosystem, requiring an alignment between the actors to let the innovation materialize.

- “the alignment structure of a set of actors with varying degrees of multi-lateral, non-generic complementarities that are not fully hierarchically controlled, providing components and complements, in order for a focal value proposition to materialise” (Adner, 2017; Jacobides et al., 2018)

Description of the Apple Store ecosystem, taken from Shipilov and Gawer (2020).

How

After having seen the definition, now I will report some of the main elements that help to identify an ecosystem from other concepts.

Among the most relevant factors, we can mention:

- Complementarities

- Three types of complementarities exist.

- Unique: The first one means that A wouldn’t function without B (and, in case of co-specialization, viceversa), requiring coordination among the actors to achieve success.

- Supermodular or “Edgeworth”: complementarities describe a relation between two objects, which can be two different products, assets, or activities, where more of A makes B more valuable.

- Generic: even though a particular good or service may be needed for the production of a complex value proposition or innovation, that good or service may be generic (i.e., standardized) enough for firms to draw on it with little concern for governance structure or risks of misappropriation.

- Three types of complementarities exist.

Ecosystems must be identified just with the first two typologies (Jacobides et al., 2018).

- Interdependencies

While complementarities represent an economic relationship in terms of the potential for value creation, interdependencies represent a structural relationship between offers, in terms of how they are connected for the value to be created (Kapoor, 2018).

In a nutshell, this means that they are even more complex to manage, because they are not directly related to an economic exchange.

To be clearer, I will report an example related to Tesla, drawn from Kapoor (2018):

- The structure of interdependencies between car producer and cell producer is distinct from the structure of interdependencies between car producer and charging infrastructure provider:

- The first one has a direct relation;

- The second one has a indirect relation, mediated by the user;

- Moreover there are other interdependencies between cell producer and charging infrastructure provider or even between charging infrastructure and the electricity grid.

Therefore, the core concern for research grounded in an ecosystem perspective is to explain firms’ strategies and outcomes through the lens of such complementarities and interdependencies.

It follows that the co-evolution of actor’s strategies represents another key element, given the kind of relationships that exist between them (Ritala & Almpanopoulou, 2017), as well as the existance of a system-level outcome (Autio & Thomas, 2021).

Finally, we should highlight that these relations between different parties are usually multi-lateral and not hierarchically or formally controlled, compared to the dyadic relations that can be found in other structures, such as supply chains, markets and networks (Adner, 2017; Shipilov and & Gawer, 2020).

As you can see, talking about ecosystem means looking beyond the strict boundaries of an organization, something that now is more needed than never, given the complex societal challenges we are facing. And this is what I like the most about this concept, as it is an example of how and why managers should adopt wider lenses to define their strategies (Adner, 2012), aligning them with all the relevant stakeholders.

I hope that this post helped to clarify (even though in a non-exhaustive way) the ongoing conversation about ecosystems.

Now, it’s time for the second episode of my column!

Surfin’ Internet

- Video:

- If you haven’t had enough on ecosystems yet, this Debate from DRUID Conference 2019 won’t let you down.

- Academic article

- In this recent article introduced by Denny Gioia, Gabriela Rivera displays all the contradictions and mixed messages PhD Students have to deal with, while embarking in the first year of their Doctoral Program.

- Tweet

- Unless you have a natural talent, writing is never easy. And writing with an academic style can be even more painful. Here you can find a nice tip to improve your writing style.

The best lesson on writing structure I've ever read: pic.twitter.com/Vx9JwMNuHv

— Nathan Baugh (@nathanbaugh27) June 22, 2022

- Unless you have a natural talent, writing is never easy. And writing with an academic style can be even more painful. Here you can find a nice tip to improve your writing style.

Bibliography

Adner, R. (2006). Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harvard business review, 84(4), 98.

Adner, R. (2012). The wide lens: A new strategy for innovation (Vol. 34, No. 9). Penguin Uk.

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of management, 43(1), 39-58.

Autio, E., & Thomas, L. D. (2021). Researching ecosystems in innovation contexts. Innovation & Management Review.

Bogers, M., Sims, J., & West, J. (2019). What is an ecosystem? Incorporating 25 years of ecosystem research. Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.11080abstract

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). The keystone advantage: what the new dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Harvard Business Press.

Jacobides, M. G., Cennamo, C., & Gawer, A. (2018). Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic management journal, 39(8), 2255-2276.

Järvi, K., Almpanopoulou, A., & Ritala, P. (2018). Organization of knowledge ecosystems: Prefigurative and partial forms. Research Policy, 47(8), 1523-1537.

Kapoor, R. (2018). Ecosystems: broadening the locus of value creation. Journal of Organization Design, 7(1), 1-16.

Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harvard business review, 71(3), 75-86.

Ritala, P., & Almpanopoulou, A. (2017). In defense of ‘eco’in innovation ecosystem. Technovation, 60, 39-42.

Scaringella, L., & Radziwon, A. (2018). Innovation, entrepreneurial, knowledge, and business ecosystems: Old wine in new bottles?. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 59-87.

Shipilov, A., & Gawer, A. (2020). Integrating research on interorganizational networks and ecosystems. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 92-121.

Stam, F. C., & Spigel, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial ecosystems. USE Discussion paper series, 16(13).

Van der Borgh, M., Cloodt, M., & Romme, A. G. L. (2012). Value creation by knowledge‐based ecosystems: evidence from a field study. R&D Management, 42(2), 150-169.

I need to to thank you for this wonderful read!! I certainly enjoyed every

little bit of it. I have got you saved as a favorite

to look at new things you post…

That’s great, I am glad it was useful!

And a new blog post is coming out 😉

What’s up, I log on to your new stuff regularly.

Your writing style is awesome, keep it up!

Much appreciated, thank you 🙂