Oppenheimer: The role of academia in technology innovation processes

As a fan of Christopher Nolan and a researcher in the innovation management field, I couldn’t help but be excited by the release of “Oppenheimer”. As you may know, the movie describes the life of the American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, focusing on his time as a student, his leadership role in the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb, and his downfall after World War II.

Atomic Bomb vs AI: similarities and differences

The movie has sparked many conversations in the public opinion about how the development of the atomic bomb resembles the dangers of an uncontrolled Artificial Intelligence (AI) use (Scientific American; Guardian; Wired). While these two innovations have some similarities, it is important to recognize their differences, too.

First, as also Nolan noted: “It’s reassuringly difficult to make nuclear weapons and so it’s relatively easy to spot when a country is doing that. I don’t believe any of that applies to AI.” Second, while AI is a broad term that covers a wide range of tools, nuclear fission is a specific chemical reaction with clear and known applications. Third, in this regard, if the atomic bomb detonation is the expected result of a process controlled by humans, most generative AI models are currently neither explainable nor predictable black boxes (repeating the same prompt may produce different results for which the machine was not even trained).

Thus, what can we learn from this movie that could still be relevant today and for future (revolutionary) innovations?

I believe that the most important takeaway is that the role of academia should not only be limited to develop innovations; rather, academics should also be actively involved in setting the rules and sensitize for a responsible use of the technology they contributed to being invented.

I will tell you more about it in the next paragraphs.

Academic activism

Nuclear activism

“This isn’t a new weapon, it’s a New World.”

After the two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Bohr’s prediction came true. The world changed forever. This is when Oppenheimer joined the already heated debate on using the bomb and began opposing the development of the H-Bomb. On this matter, he says in the movie that:

“Having played an active part in promoting a revolution in warfare, I needed to be as responsible as I could with regard to what came of this revolution.“

However, this position turned to be more problematic than expected. Several scientists that played a key role during the war were increasingly excluded from influential positions when it came to the future of atomic energy, due to their criticism (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists). For Oppenheimer, this period reached its peak with the loss of his security clearance (Avalon Project). Nonetheless, academia managed to play a vital role in regulating atomic energy.

Particularly, Linus Pauling, an American chemist that received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954, had a huge influence on the U.S. public opinion in the disarming process and ban of nuclear weapons tests. In 1958, together with his spouse, he submitted a formal petition to the United Nations, urging the cessation of nuclear weapons testing. This document was signed by 11.021 scientists representing fifty countries. Moreover, Pauling also supported the research known as the “Baby Tooth Survey”, which provided legitimacy and a crucial boost to public opinion demands (Wikipedia).

Public pressure and the results of this research contributed to the signature of the moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, between John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. For his activism, Pauling received in that year the Nobel Peace Prize, which made Pauling the only person to have been awarded two unshared Nobel Prizes.

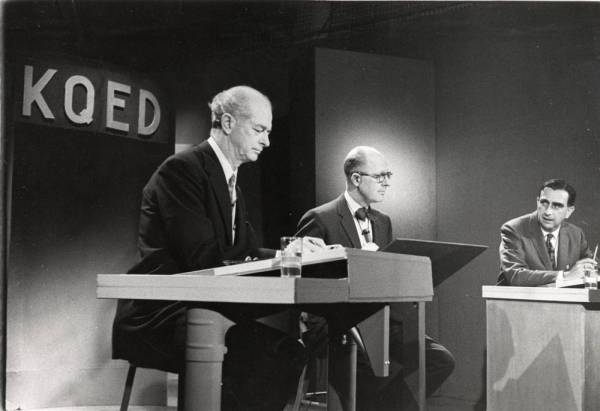

Pauling and Teller TV debate Source: Oregon State University

Other examples

Nevertheless, this is not an isolated case. The scientific community has played a pivotal role in regulating scientific innovations in other instances, too. The regulation of genetic engineering is another example (Krimsky, 2005).

The first publications describing the successful production and intracellular replication of recombinant DNA appeared in 1972 and 1973. Recognizing both the benefits and risks of this innovation, a group of experts (mainly biologists, but also including lawyers and physicians) met at Asilomar in 1975. During this conference, the experts discussed these concerns and a voluntary moratorium on recombinant DNA research was introduced for experiments that were considered particularly risky. These guidelines eventually informed the regulation set by the National Institutes of Health (USA) in the following years, which formally limited rDNA applications (Wikipedia).

Conclusion

The development of new technologies is leading us into an era of rapid transformation across various aspects of our lives. From Large Language Models to Blockchain, the pace of change is accelerating, while regulations often struggle to keep up (GZero).

In light of this, it is evident that academia’s role extends beyond just fostering the development and commercialization of new technologies. It also involves championing a responsible approach to innovation.

Engaged scholarship is a great starting point to increase the likelihood of advancing knowledge for science and practice (Van de Ven, 2007). However, as we have seen, sometimes the role of experts and citizens blur (Hoffman, 2016), making it necessary to reach another level of engagement: an engagement that leads to moving beyond the ivory tower of academia.

References

Hoffman, A. J. (2016). Reflections: academia’s emerging crisis of relevance and the consequent role of the engaged scholar. Journal of Change Management, 16(2), 77-96.

Krimsky, S. (2005). From Asilomar to industrial biotechnology: risks, reductionism and regulation. Science as Culture, 14 (4), 309-323.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford University Press, USA.

Add a Comment