How thinking about publishing can help your research

You are probably wondering why a first-year PhD student is already talking about how to get published. Even though my natural thought has always been to think about publishing after actually having written something, I have attended a course on How To Get Published taught by Prof. Dries Faems which has shown me otherwise.

As PhD students, and Early-Stage Researchers at EINST4INE, we should be able to recognize and apply the basic structure of an academic text, which includes an abstract, an introduction, a literature review, a method section, and a conclusion (at the least). This might differ according to the nature of our research, different journals might have different requirements – but the truth is that the academic world is competitive, so you might as well start now.

First, before you fit your paper into a specific journal, ask yourself these questions:

- What is your research question?

- How is your research question related to the current literature?

- How will you use your data to answer your research question?

These are questions that both, author and reader need to be able to answer.

The next step would be to choose a journal.

After having established what kind of paper you are planning to write (conceptual, quantitative/qualitative, positivistic/interpretative), you will probably recognize the community of scholars who are working and have published in your line of study, and thus you can identify which people should read your work, and where they have published.

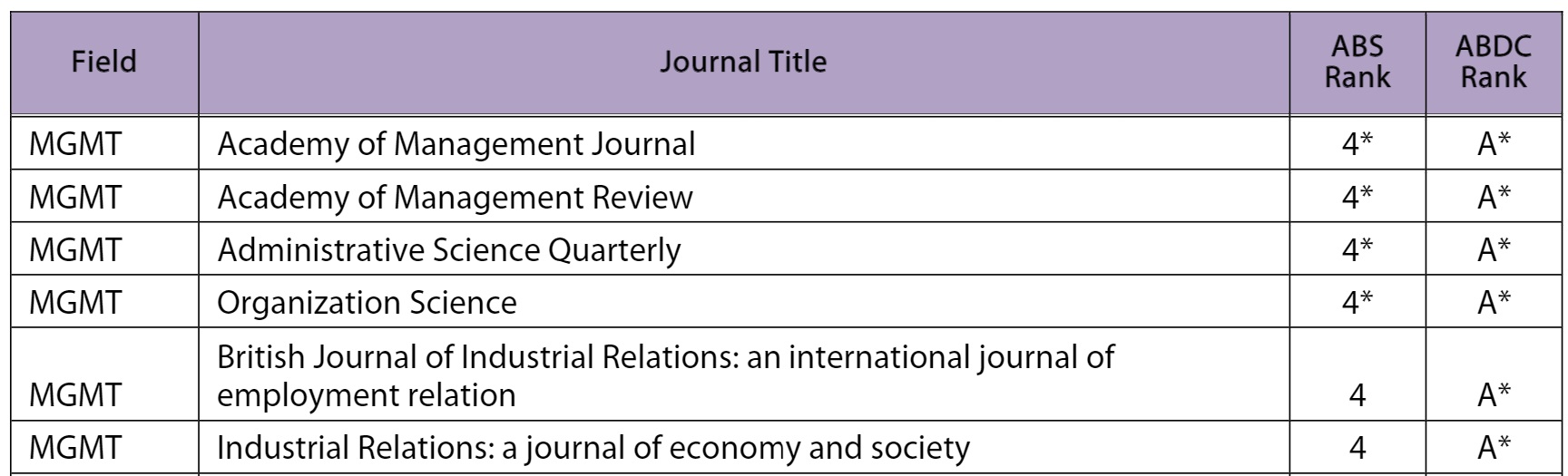

There are a number of websites and services which publish journal rankings according to their impact factor. Here, the impact factor represents the frequency with which an average article in a journal within a given year has been cited. Counting the number of times its articles are mentioned, determines the standing or prominence of a journal.

Example of the ABS ranking for Management (MGMT) journals [Image source: ABS (Association of Business Schools) and ABDC (Australian Business Deans Council)].

Then, another useful step would be to get to know the editors of the journals as well as assess the reputation of these journals in terms of processing time/quality of the feedback that they give (don’t forget to check the Open Access criteria/options). This can be done by contacting people that have had experience with the journal. You might also find that you want to target other journals which are not included in the big journal list but are still very relevant to your field of study. For instance, as a Management scholar, I might focus on the Academy of Management Journal (impact factor 10.2). But with a specialization in ecosystem research, the R&D Management (impact factor 4.3) Journal might also be a great fit.

Once you have made your selection of qualified journals, start writing your paper with the criteria of the journal in mind. This has definitely helped me not only to narrow down the most crucial sources of information for my research but also helped me find a research focus.

… So how do you write a paper that might get accepted?

According to Prof. Faems, there are a number of reasons a paper might get rejected, one of them simply being the reason that the paper does not fit the personality of the journal, emphasizing the need to work towards that target journal. Some other reasons include an absence of a clear theoretical contribution, a lack of novelty, and methodological issues.

Unfortunately, I don’t think there is a specific recipe that mixes a set of ingredients for success. But there are still some basic ingredients that might help:

- Clearly position your project against existing research and theories

- Formulate a good theoretical contribution

- Good data and methodology won’t hurt

The best way to understand how you can embed your project in existing research is to visualize it:

Imagine you are entering a house and you have to choose to enter a room, which goes in line with your research. So, you enter the room of Management research. You try to find a table of people who you understand and where you feel comfortable enough to contribute to the conversation. So, you go sit at the table that talks about, let’s say Open Innovation. So, you’ve already positioned yourself in the Management field, focusing on Open Innovation. At the Open Innovation table, you are trying to recognize the recurrent themes and findings that are being reported and you identify the most important people at this table.

Once you have done that, you might be able to recognize missing links in the current research or you might make new links that you wish to develop in your research.

One challenge that many scholars and reviewers report is the clear positioning in one specific area of research. For instance, while I can identify a particular gap in the Open Innovation literature, I realize that I can address this gap with findings from the Ecosystem literature (for instance), which puts me at two different tables in my Management room. In this case, making links between two literature streams is good, if I make it clear. However, the more links I have, the more delicate it becomes and can confuse some people at my main table.

In terms of the novelty of the paper, reviewers are often looking for interesting ideas that have the potential to impact future research, i.e. a strong contribution. This process seems tricky, as novelty does not necessarily mean interesting. Imagine you have found a research gap in your given field… This doesn’t imply that it’s a novel idea, it might well be an idea that has already been thought of but is not worth researching further. Thus, an editor might reject your paper on the basis of lacking a novel and relevant contribution. This is the reason why having good data doesn’t hurt. While your theoretical part might lack some grounding and novelty (which, for the record, it shouldn’t), having a unique and well-developed dataset that is difficult to access, can become an advantage during the review process.

The theoretical grounding, novelty, and contribution of your research, along with your data (depending on the nature of your research) are the main selling points of your research, which should be communicated at the beginning.

And the best way to communicate it is through the introduction, which is the gateway to a good paper. Indeed, apart from the abstract which swiftly summarizes your research, the introduction is one of the most important written parts of your research. In fact, editors make a first judgment based on the quality of the introduction which should include:

- The community you want to talk to

- Your research gap

- How you address the research gap

- Your main findings and contributions

Of course, this does not mean that one should disregard other sections like the discussion section, where you can go more in-depth into discussing the implications of your findings and iterate on the practical and theoretical contribution you wish to make.

Finally submitting it…

Once you think you have managed to position your research in a clear and concise manner, the last step is to get some friendly reviewers (such as fellow researchers, supervisors, etc.) to look over your work before submitting it to your journal of choice.

And then you wait…

You will most probably receive feedback from the editor with reviews from researchers in the same or related field (some that might even be cited in your paper!) who will either have immediately rejected it or might have accepted it with some changes. This return can provide you with a relevant critique on how to improve your paper, and (hopefully) arm you with the tools necessary to survive the next round of reviews and get you published.

I hope I was able to provide a little insight into what I have learned about publishing and how I aim to tackle my research. Of course, there are different ways to conduct research and get published. I have certainly started following my own advice from this post, which was mostly inspired by what I have learned following Prof. Faems’ How to Get Published course.

And who knows, this might even be helpful for becoming a good reviewer or even editor at some point…

Add a Comment